The cost of housing, Hawaiʻi’s top expense, has skyrocketed since 1980

Hawaiʻi residents have been coping with a high cost of living for decades. By 2018, however, making ends meet was a bigger problem for more people than ever before.

While other expenses have also increased for Hawaiʻi households, housing costs are by far the most expensive item in most household budgets. Housing costs have also grown by far more than any other household cost—an extraordinary 79 percent increase between 1980 and 2018.

The monthly expense for rent and utilities for a one-bedroom apartment at fair market-rate in Honolulu was $1,527 in 2018, compared to $853 in 1980 after adjusting for inflation. This means the 2018 household budget had to cover an additional $8,100 per year just for shelter.

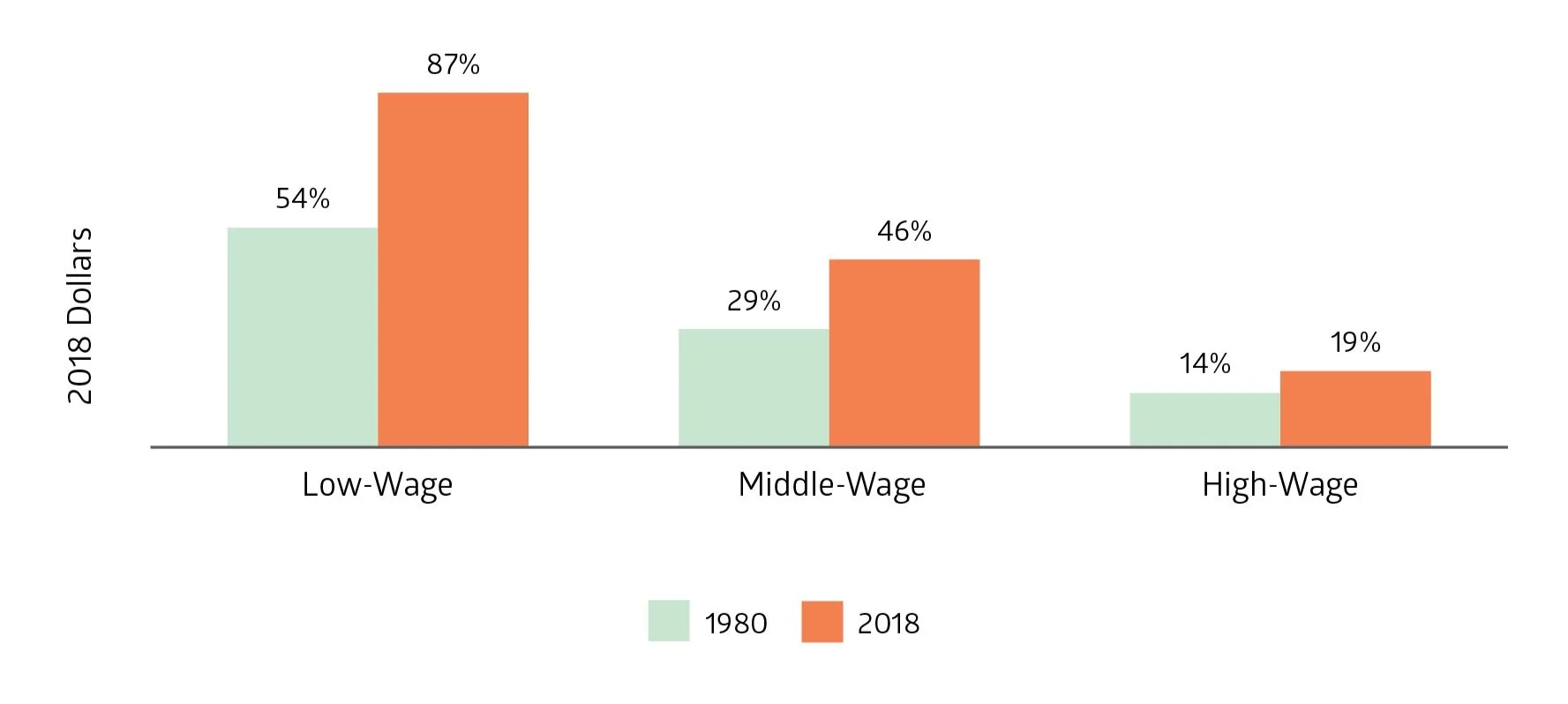

Figure 1. Portion of Wages Needed to Rent a 1-BR, Market-Priced Apartment, 1980 vs 2018

Figure 1. The cost to rent a market-priced 1-bedroom apartment with utilities has increased more than wages at every income level. The gap reflects both escalation of rents and stagnant low- and middle-wages.

Between much more expensive rents and sluggish wage growth, low- and middle-wage workers now have to put a greater portion of their salaries aside to cover housing. Even high-wage workers devote more of their salaries to rent. Figure 1 shows the percentage of salaries that workers paid to cover rent in 1980 compared to 2018. The calculations reflect changes in both wages and costs.

Figures 2 and 3 show additional ways to look at the divergent growth trends for wages and housing. Only the pay for high-wage workers grew enough to cover the significant increase in housing costs.

Figure 2. Increases in Low- and Middle-Wage Earnings Have Not Kept Up with Increasing Housing Costs

Figure 2. Compared to 1980, low-wage workers earned just $2,000 more per year in 2018 compared to 1980 but faced significantly higher basic costs of living. Middle-wage workers gained $4,500, while high-wage workers saw a pay increase of $25,230. The cost for housing alone increased by nearly $8,100.

Figure 3. Hawaiʻi Monthly Housing Costs Compared to Low-Wage Monthly Salary Over Time

Figure 3. While the pay for low-wage workers increased by 11 percent between 1980 and 2018, the cost to rent a one-bedroom apartment at the fair market rate increased by 79 percent. In 1980, rent consumed 54 percent of a low-wage salary. That cost climbed to 87 percent by 2018.

Rents have been a larger burden in Hawaiʻi than in other parts of the U.S. for a long time: in 1980, Hawaiʻi’s rents were the second highest in the country, and now Hawai‘i is the most expensive rental market. A similar trend in increased rents is evident in many cities across the county, but on average, the cities with the highest rents also pay the highest average salaries. This is not the case for Honolulu. In fact, after adjusting for the cost of living, average wages in Hawaiʻi are the lowest in the nation.

This is a primary financial pain point for Hawaiʻi working families, roughly half of which are living paycheck to paycheck and struggling to survive.

According to the “Hawaiʻi Perspectives” spring 2019 report, 74 percent of residents surveyed said, “There is not enough housing that local Hawaiʻi families can afford, putting home ownership out of reach for too many.” In addition, 71 percent said, “The cost of living, such as the high cost of groceries and utilities, makes it hard to live here, let alone put money in savings.”

The survey also reported that, “An alarming 45 percent of residents are choosing to leave Hawaiʻi or considered doing so. Two-thirds of 18- to 34-year-olds have considered leaving or have a member of their household who has considered leaving or left the state.” This is borne out by data that shows an acceleration of migration away from Hawaiʻi after 2010, as shown in Figure 4.

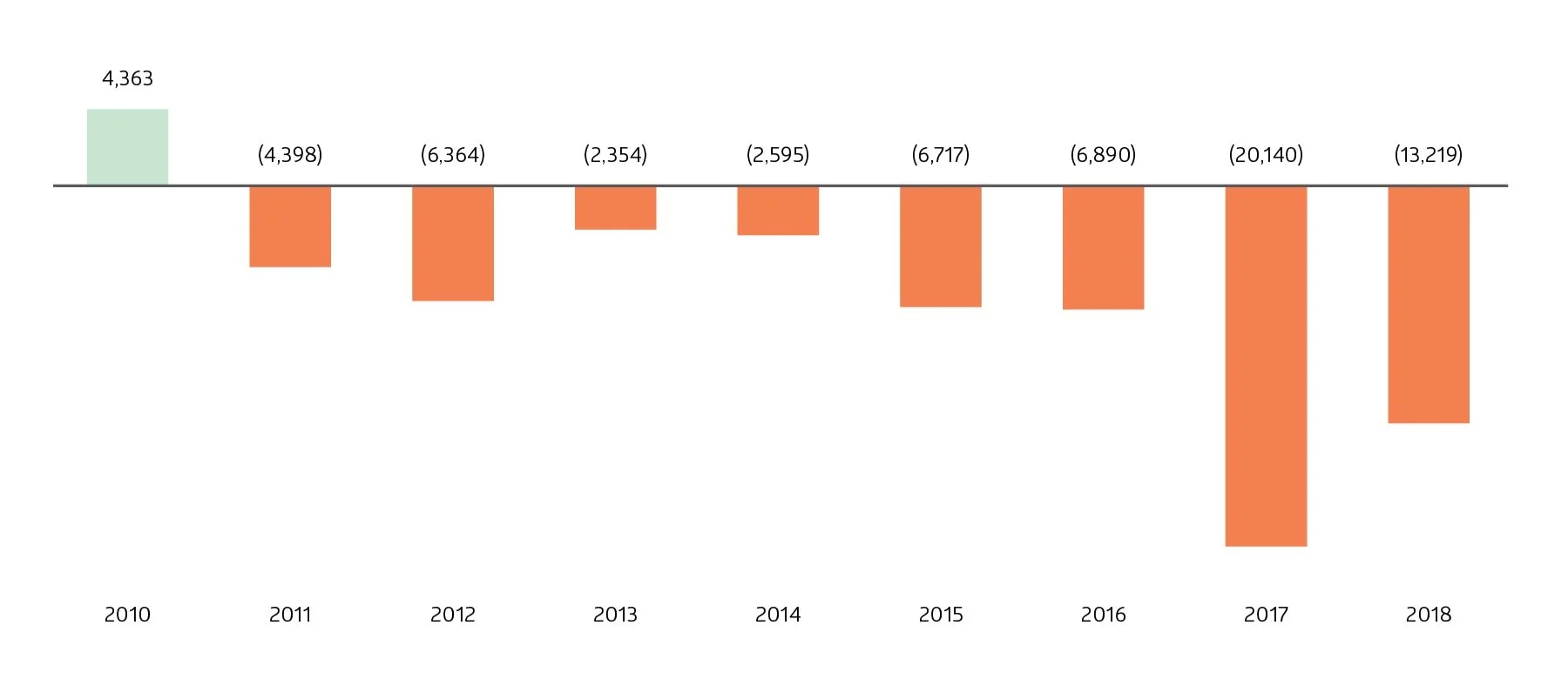

Figure 4. Hawaiʻi’s Net Domestic Migration, 2010–2018

Figure 4. Migration of residents away from Hawaiʻi increased after 2010.7 “Net migration” is the difference between intended residents arriving from and current residents departing for other states and territories. Compared with the general population, out-migrants have lower incomes and are more likely to be non-elderly adults, better educated, and renters rather than homeowners.

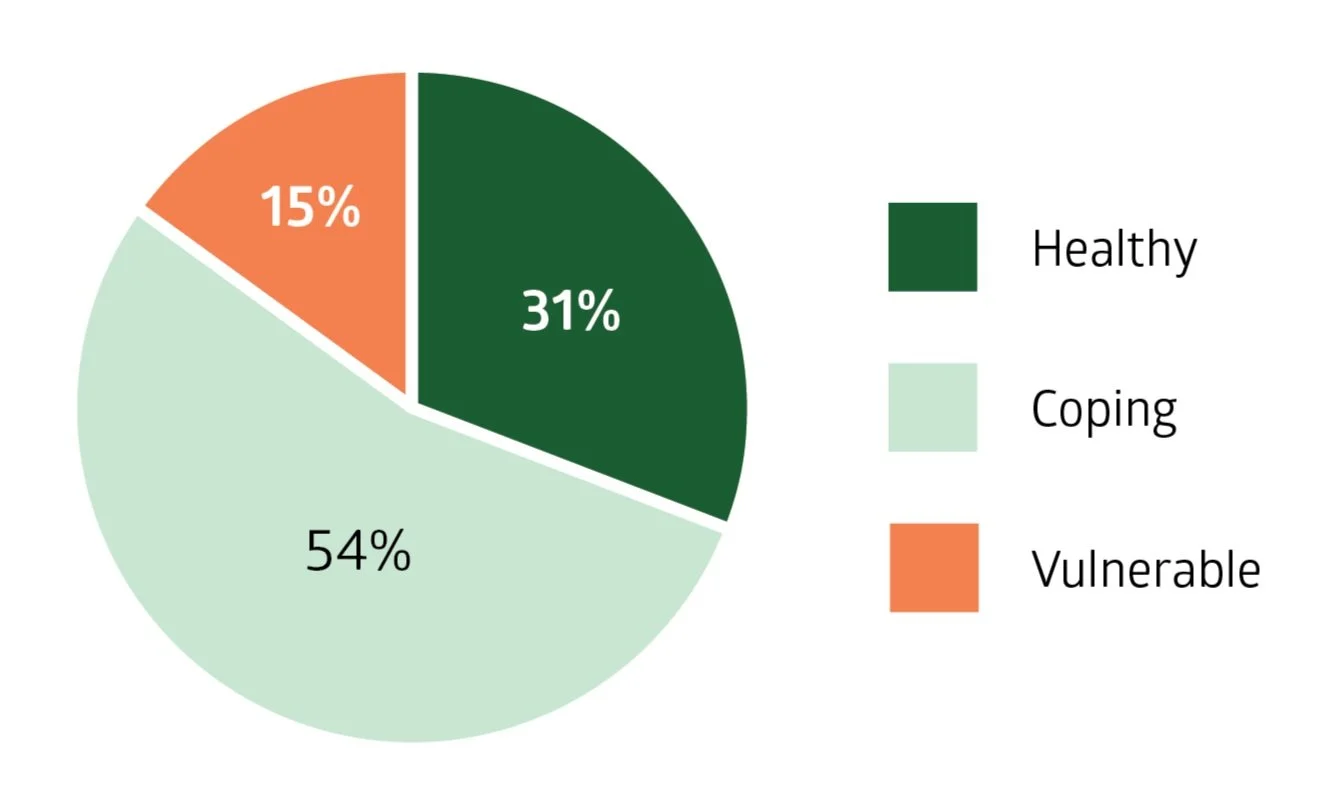

Adding another caution about Hawaiʻi’s economy, the “Hawaiʻi Financial Health Pulse 2019 Survey” detailed the large number of financially struggling families. The survey found that only 31 percent of households in the state were financially healthy, as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Hawaiʻi 2019 Households Financial Health

Figure 5. The Hawaiʻi Financial Health Pulse 2019 Survey8 reported that 69 percent of Hawaiʻi residents struggled financially. The report noted that for 54 percent of Hawaiʻi residents spending equaled or exceeded their income, and nearly a quarter (23 percent) worked more than one job. Only 31 percent spent less than they earned, paid bills on time, and had both liquid and long-term savings, manageable debt, and appropriate insurance.

Every other year, the state Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism issues a report on self-sufficiency standards that reflects the cost-of-living for households of different sizes where the adult members are working. The study defines economic self-sufficiency as “the amount of money that individuals and families require to meet their basic needs without government and/or other subsidies.”

In 2018, the monthly self-sufficiency budget for a single adult amounted to $3,029. In order to cover this most basic of budgets, a worker would have to earn $17.48 per hour, or 73 percent more than the current minimum wage of $10.10. For a family composed of two adults, a preschooler, and a school-age child, the monthly self-sufficiency budget was $6,921. The adults in the household would have to earn a combined $40 per hour to cover these costs. Self-sufficiency budgets are shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6. Monthly Self-Sufficiency Budgets, 2018

Figure 6. In 2018, the cost of housing accounted for half of the monthly selfsufficiency budget of a single adult. For working families with young children, the household’s biggest expenses are for rent, food, and childcare and/or private preschool.