Now is the right time to expand Hawaiʻi’s Earned Income Tax Credit

The Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) is a special tax credit designed to let working families keep more of the money they earned through their work. It’s a critical tool for lifting workers who are paid low wages—and especially those with children—out of poverty, and it is a highly effective economic stimulus as well, contributing up to $1.24 in economic activity for every $1 returned to workers as part of the EITC.

Many of the workers eligible for an EITC do not earn enough to cover all their basic needs, including food, housing and healthcare. The credit helps these workers provide their families with the basics and makes the tax system more equitable in the process. Research on the EITC shows that the credit contributes to long-term economic and health gains for families.

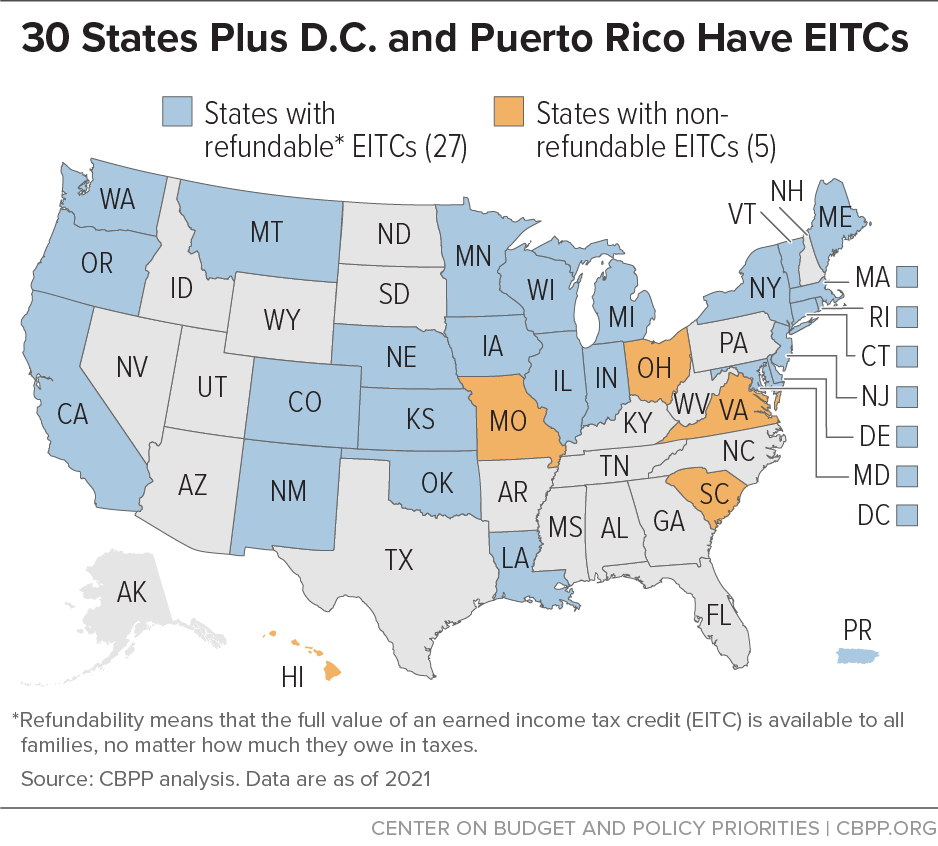

In 2021, 12 states plus the District of Columbia created or expanded their state’s EITCs. These jurisdictions recognized the devastating effects of the pandemic recession and improved their EITCs to support their working families. Hawaiʻi should join them.

Some of these states increased the amounts of money that families could get from their EITCs or made their EITCs refundable. Others extended eligibility for the EITC to more people, such as younger or older taxpayers and Individual Taxpayer Identification Number (ITIN) holders. Some did both.

When the federal American Rescue Plan (ARP) passed in March 2021, there was some concern that language that forbade states from using ARP funds for tax cuts also meant that increases in tax credits for working families, like the EITC, were also forbidden.

In January 2022, the IRS published a final rule that reassured states that they are allowed to increase their EITCs without running afoul of the ARP language. And the 12 states plus D.C. that went ahead and increased their state EITCs during their 2021 legislative sessions help to prove that point.

The IRS final rule is a dense 437 pages. Here are a few sections of language in the rule that are relevant to expanding state EITCs.

First, the excerpt below explains that states do not need to identify other sources of funding to pay for revenue reductions, if those reductions are less than one percent of the reporting year baseline, which is FY 2019. It seems likely that the cost of making Hawaii’s EITC refundable would be below that level:

If the total value of the revenue reductions resulting from these changes is below the de minimis level, the recipient government is deemed not to have any revenue-reducing changes for the purpose of determining the recognized net reduction…. the de minimis level is calculated as 1 percent of the reporting year’s baseline. (p. 330)

Treasury determined that the 1 percent de minimis level reflects the historical reductions in revenue due to minor changes in state fiscal policies and was determined by assessing the historical effects of state-level tax policy changes in state EITCs implemented to effect policy goals other than reducing net tax revenues. (p. 332)

In addition, the IRS final rule explains that states are not subject to this requirement to find other revenue offsets if state revenues come in higher than they were in FY 2019 (adjusted for inflation). The most recent Hawaiʻi Council on Revenues projections indicate that will likely happen in FY 2022:

If actual tax revenue is greater than the baseline, Treasury will deem the recipient government not to have any recognized net reduction for the reporting year, and therefore to be in a safe harbor and outside the ambit of the offset provision…. If net tax revenue has not been reduced, the offset provision does not apply. (p. 332)