Hawaiʻi’s housing market is a nightmare for working families; it doesn’t have to be

For more on state of Hawaiʻi’s housing market and recommendations for improving it, see the Hawaiʻi Budget & Policy Center brief, Building a Housing Market for Hawaiʻi’s Working Families.

For a majority of Hawaiʻi residents, the prospect of owning a home—or even finding an affordable place to rent—is increasingly out of reach. High housing costs, a low supply of affordable units, and an influx of wealthy out of state investors all work in conjunction to limit opportunities for housing security, especially for residents with the lowest incomes who must compete for scarce housing in an increasingly costly market.

Not only does this impose steep costs on family pocket books, it also pushes many long-term residents out of state in search of affordable housing opportunities elsewhere. While we’re not going to solve our housing crisis overnight, it’s important to examine how we got here and what policy choices we can make to move us toward greater housing opportunities for all residents.

Hawaiʻi has long had one of the highest cost real estate markets in the country. The state’s first quarter 2021 median home price of $615,000 put the state well above the national median of $369,800. On Oʻahu, the median shot up to over $1 million in 2021, representing a 22 percent jump relative to the previous year.

But it isn’t just home-buying that remains increasingly out of reach—it’s also finding an affordable place to rent. Monthly fair-market rent for a 2-bedroom unit ranged from $1,531 in Hawaiʻi County to $2,240 in Honolulu County. The U.S. average for a similar unit is just $1,295.

One major driving factor behind our costly housing market is our low supply of units, relative to our high demand. Hawaiʻi remains an enticing market for wealthy, out-of-state investors and visitors, who compete for the same scarce resources as permanent residents. From 2017–2020, out-of-state buyers represented nearly one quarter of all homes sold in the state.

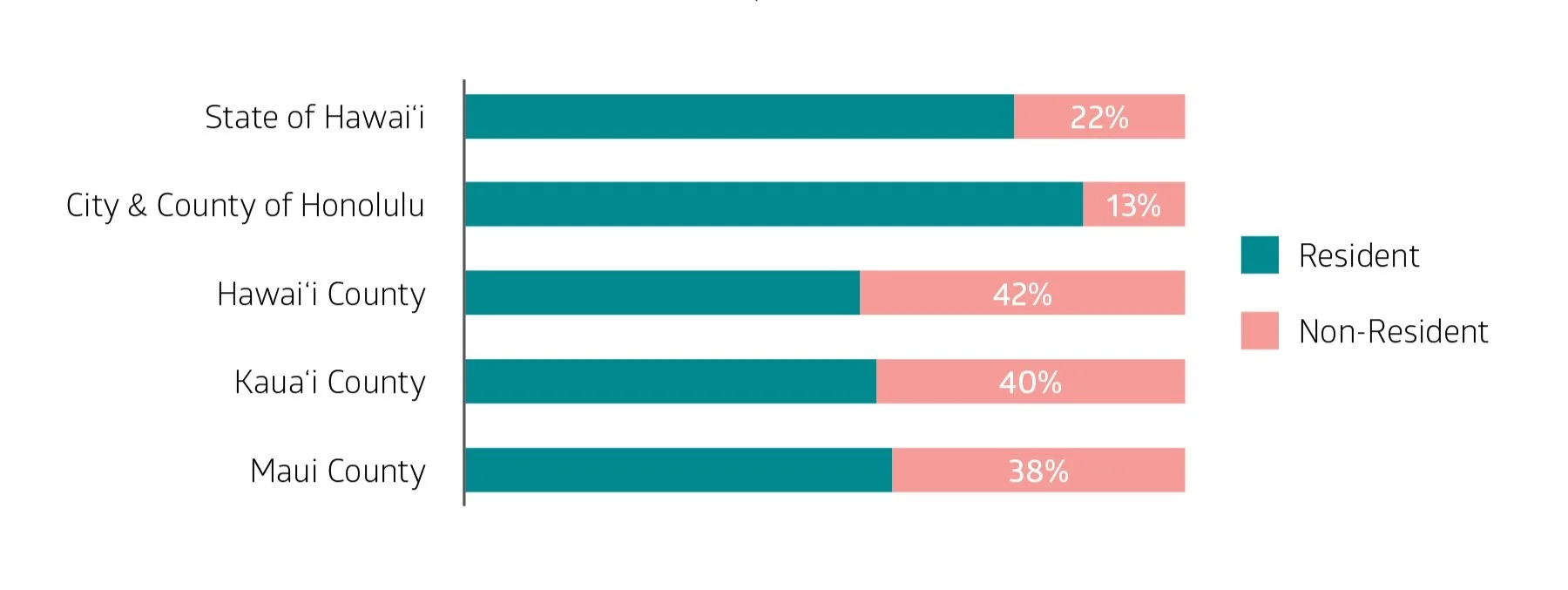

The percentages become even more stark when looking at certain counties. While, in Honolulu, out of state buyers represented only 13 percent of homes sold, on Kauaʻi and Hawaiʻi Island the share of out-of-state buyers was as high as 40 and 42 percent, respectively. These high percentages of out-of-state buyers take already scarce housing off the market, further constraining supply and driving up housing costs for residents.

Figure 1. Percent of Hawaiʻi Homes Purchased by Non-Residents, 2017–2020

This housing crunch becomes particularly acute for households with low and moderate incomes. According to the National Low Income Housing Coalition, for households earning 100 percent of the Area Median Income (AMI)—$106,000 for a family of four—there are only 89 rental units available at an affordable rate in 2021. For households earning 30 percent of AMI there were just 38 affordable units available. At the same time, other units that are either unaffordable or not on the rental market at all remain vacant.

Figure 2. Vacant Housing: Hawaiʻi vs U.S. Average, and Among Houses Built in Hawaiʻi from 2014–17

The low supply of rental units affordable to low-income families is a result of an increasingly tight housing market that continues to drive prices up and out of reach for them. This also drives up the cost of housing in general. Current surveys show that 54.6 percent of all Hawaiʻi residents are now “cost burdened,” meaning they spend 30 percent or more of their income on housing. For families with low incomes (households earning 51-80 percent AMI), the cost-burdened figure jumps to 63 percent of households.

The good news is there are policy choices we can make as a state to prioritize housing security for all residents. Namely, leveraging the public sector’s resources to drive the development of more affordable housing, while also working to keep costs low. Developing housing on public lands can significantly lower construction costs, as the state and counties already own multiple parcels.

Similarly, public financing of development through municipal bonds can help to maximize the power of already existing subsidies like the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit (LIHTC), which is the primary driver of affordable housing development across the country.

Additionally, counties should consider targeted tax policies, such as an additional tax on owners of second homes and vacant investment properties to service bond debt or invest in other pre-development and development costs.

While the legislature has previously signaled its intent to invest in affordable housing, the investments made to date are clearly not enough. If policy makers are serious about addressing our housing crisis, these investments will need to be larger and sustained over longer periods of time if we’re going to build truly affordable housing and create a market that works for Hawaiʻi residents.