Hidden data: the untold story of Native Hawaiian children in foster care

To many people, data may seem like just a collection of numbers put together in tables and graphs with no real impact in the everyday world. However, by collecting, analyzing and disaggregating data, we can untangle and examine the different strands of our collective narrative and create more nuanced and effective policy. Because data influences government investments of tax revenue, data disaggregation provides a voice to the voiceless and representation to the disenfranchised.

One story that deserves particular attention is that of the fate of children placed in the care of the Hawaiʻi Department of Human Services (DHS) Child Welfare Services Branch (CWSB). This is especially important for indigenous children because they are dramatically over-represented in the foster care system. As of 2019, 1,238 of children in foster care—45 percent of the total—were full or part Native Hawaiian. In comparison, the 2010 Census reported that just 34 percent of all the children under age 18 in the state were Native Hawaiian.

Figure 1. This graph shows the rate of Native Hawaiian children in foster care over the last 5 years. Unfortunately, CWSB has not provided detailed data for other ethnicities to the public prior to 2018.

Figure 2. Disaggregated foster care data from 2019, after the agency began more detailed collection and reporting of data.

In the Hawaiʻi Budget & Policy Center publication, Data Justice: About Us, By Us, For Us (2021), we outlined the importance of state agencies developing targeted solutions for populations that disproportionately interact with their services. CWSB has recognized Native Hawaiian children as a vulnerable group for services for families and children. The agency has created multiple partnerships to support cultural programs and has emphasized a commitment to improving care for indigenous children in its Child and Family Services Plan for 2020-2024.

The following initiatives provide just a sample of the wealth of knowledge, cultural resources and capacity the Native Hawaiian people have to develop solutions for children to heal and build resiliency—especially for those children in foster care. For example, Native Hawaiians have ancestral practices of hānai and luhi to help build support networks for foster care children. Connecting children to the Native Hawaiian culture can help to build identity, security and strength for children to draw upon in the future.

Ka Pili ʻOhana. To help reduce the number of Native Hawaiian kamaliʻi (children) entering foster care, and to help transition them more quickly to permanency with their ʻohana (families) or other permanent caregivers, Liliʻuokalani Trust (LT) has partnered with CWSB, Family Programs Hawaiʻi, Child and Family Services, and other providers to develop Ka Pili ʻOhana (KPO). KPO is a community-based, culturally grounded program designed to achieve better outcomes for Native Hawaiian kamaliʻi in foster care.

Wahi Kanaʻaho. Although a program of the Juvenile Justice System, half of the youth in the program are also foster youth. Situated in the Waiʻanae Valley of Oʻahu, it is a 21-day residential program for youth run by a local Native Hawaiian cultural practitioner. The curriculum revolves around the Hawaiian cultural practice of hoʻoponopono, a self-reflective process that emphasizes healing and strengthening relationships to restore balance in one’s life. Through the program, youth learn to plant kalo (taro) and other crops, which is a powerful physical metaphor for healing.

Ke Kama Pono (KKP). A residential safe house for teen law-violators run by Partners in Development Foundation, KKP incorporates Hawaiian practices into its activities. Over a three-year period, the recidivism rate for youth who left the program was 37 percent, based on internal data analysis. This compares favorably to the 75 percent recidivism rate for the same period for youth who exited from the Hawaiʻi Youth Correctional Facility.

Hui Hoʻomalu. In 2006, the State of Hawaiʻi Department of Human Services (DHS) awarded a master contract to Partners in Development Foundation (PIDF) to help enhance and advance Hawaiʻi’s foster care system. As a hui, this statewide initiative addresses the identification, recruitment, screening, assessment, training, ongoing support and retention of resource families for children and families that are in the care of DHS.

Needed Areas of Data Disaggregation

Hawaiʻi Budget & Policy Center’s initial analysis of CWSB’s data collection and analysis finds that the agency either does not publicly provide or does not collect data that disaggregates ethnic/racial data for key indicators that would reveal the story of Native Hawaiian children in the system. The public cannot ensure that CWSB has set appropriate goals and is accountable for them without knowing why Native Hawaiian children are taken away, who fosters them, and what happens to them after exiting foster care. To see the full picture we can begin by addressing the following questions and indicators:

#1. Why are Native Hawaiian children being removed from their parents?

If we track the rates of confirmed cases by race/ethnicity, we can see if there is bias in the reasons given for why Native Hawaiian children are removed from their parents. If Native Hawaiian children are more likely to be placed in foster care for lesser offenses, the CWSB’s implicit bias may contribute to overrepresentation of Native Hawaiian children in foster care.

Bias against Native Hawaiians in CWSB would not be unique, as studies have extensively documented bias against African American and Native American families. Symptoms of bias are seen in overrepresentation of these groups in system reporting, investigating, placing children into foster care, the length of time that children are in the system, and whether children re-enter the system.

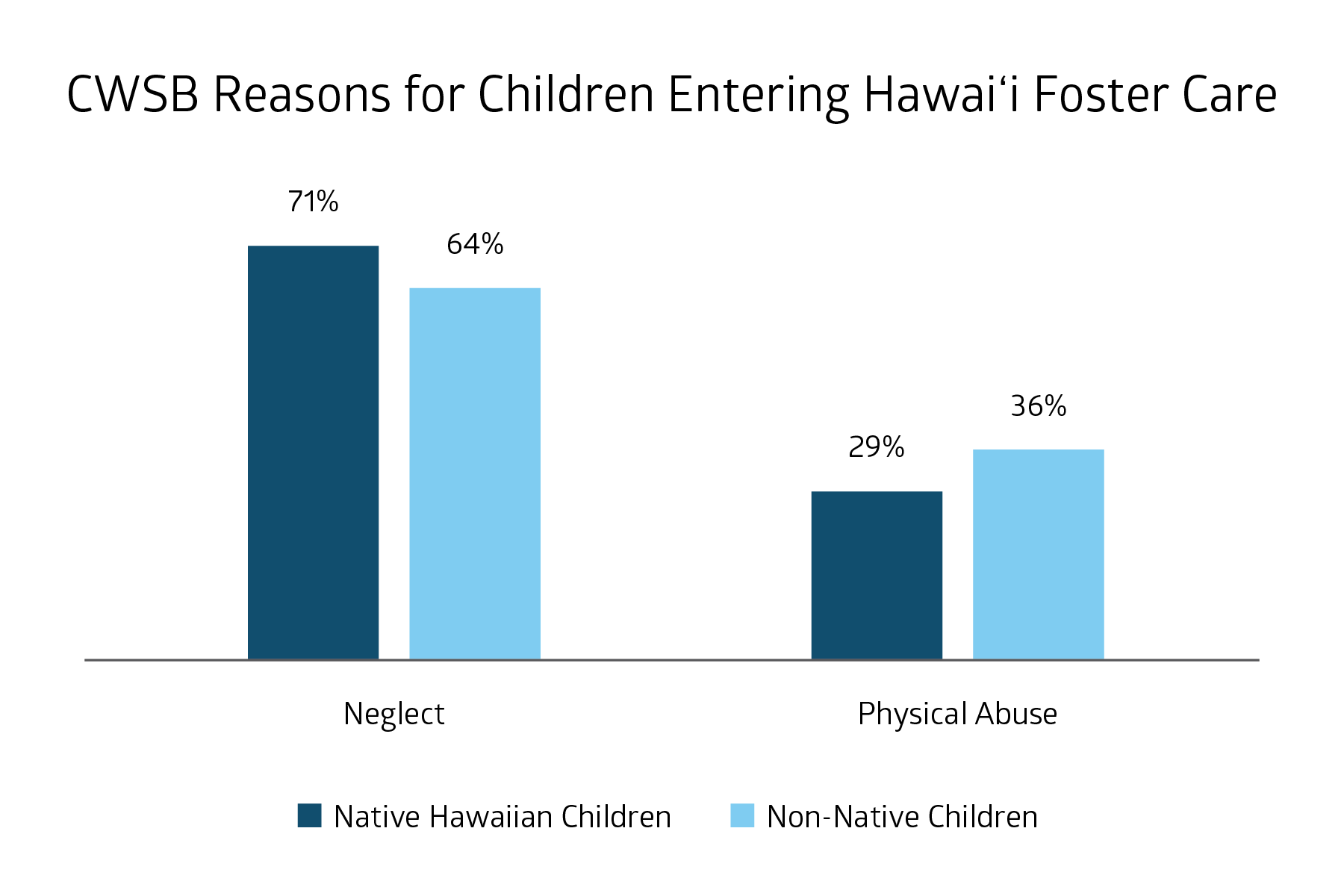

A 2011 study by Meripa T. Godinet, et al. on Hawaiʻi DHS’s CWSB data from 2004–2005 found that Native Hawaiian children entered foster care because of neglect at a higher rate than non-Hawaiian children, but at a lower rate because of physical abuse.

Analysis of CWSB reports shows other areas where bias could affect subjective decisions. For example, factors that caseworkers use to justify removal include parents’ “inability to cope with parenting responsibility;” inadequate housing; insufficient income or misuse of income in the home; and “broken families.”

Figure 3. CWSB data from 2004–2005 shows that Native Hawaiian children entered foster care because of neglect at a higher rate than non-Hawaiian children, but at a lower rate because of physical abuse.

#2. Who fosters Native Hawaiian children?

Over 50 percent of children are placed with relatives when they enter foster care, but CWSB annual reports do not share the percentage of Native Hawaiian children who are placed with family members. Are Native Hawaiian children just as likely to be placed with relatives? If not, does bias color the viewpoint of Native Hawaiian relatives being less capable? And, when Native Hawaiian children cannot be placed with relatives, how often are they placed with resource caregivers (foster parents) who are Native Hawaiian?

Only 34 percent of foster parents are Native Hawaiian, compared to the 45 percent of foster children who are Native Hawaiian. As the Office of Hawaiian Affairs explains, “many of the available Resource Families are military, so Hawaiian keiki may be placed in homes where everything is unfamiliar: language, food, rules, customs and expectations.” CWSB has committed to improving recruitment of Hawaiian resources families, but the public cannot hold the agency accountable without access to more detailed data for evaluation.

#3. Where do Native Hawaiian children go when they leave foster care?

Only 62 percent of foster care children were reunified with parents in 2019, but disaggregated ethnic/racial data is not available for this indicator in CWSB’s public annual reports. Disaggregated data is also unavailable for the average length of stay in foster care or rate of reentry. As a result, it is impossible to see if Native Hawaiian parents are held to the same standard as other families, or whether they have to somehow “prove” themselves more.

Although CWSB’s priority is reunification of children with parents, many children are adopted each year. Having disaggregated information about the ethnic and racial makeup of adoption matches is crucial because adoption of a Native Hawaiian child by non-Hawaiian parents can terminate resources that connect the child to their culture. Over a decade ago, adoption of Native Hawaiian children by non-Hawaiian military families was significantly high, and resulted in children moving away from Hawaiʻi.

In 2019, out of all children leaving foster care, 193 (16 percent) were adopted and 179 (15 percent) were released to a guardian. However, CWSB does not offer racial/ethnic data of the child and adopted parent to the public, instead they send adoption data to the federal U.S. Children’s Bureau, which lacks adequate data disaggregation. The federal agency’s latest information provides only racial/ethnic data for adopted children; however, this statistic does not disaggregate Native Hawaiian from other Pacific Islander, nor children who identify as more than one race.

Figure 4. The U.S. Children’s Bureau provides only racial/ethnic data for adopted children, but does not disaggregate Native Hawaiian from other Pacific Islander, or children who identify as more than one race.

The U.S. Children’s Bureau also publishes the type of relationship between the adopted child and adoptive parents. Out of all adopted foster children, 62 percent were adopted by relatives, 33 percent were adopted by foster parents, and 5 percent were adopted by non-relative, non-foster parents. However, we still lack data on adopted parents’ race and ethnicity. Who are the adopting foster parents or the non-relative, non-foster parents?

Next Steps

The lack of disaggregated ethnic/racial data is not unique to CWSB, instead it is a common problem among state government agencies, as we found in our data justice report. However, CWSB is responsible for the care and wellbeing of an extremely vulnerable group of children. By implementing data practices that make more detailed information available to the public, we can hold the state accountable for addressing the disproportionate rate of Native Hawaiian children in foster care.

To move forward more effectively and efficiently, the state should prioritize new data systems and transparency. The Department of Human Services received $6.6 million for COVID-19 IT infrastructure Systems, which has not been spent. CWSB serves some of our most vulnerable children, and they need our help. It should be DHS’ priority to spend some of this money for IT improvements that will help CWSB set its service goals and allow the public to see how well they’re meeting them.