What makes a good tax system?

On October 17, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy (ITEP) published its newest edition of Who Pays?, a report that analyzes vital statistics from tax systems across the United States. The report concludes that, with few exceptions, state tax systems in America exacerbate inequality and widen the gap between rich and poor through system-wide tax policy decisions. A combination of different taxes used to collect revenue from the population—sales and use taxes, income taxes, property taxes and others—together, make up a state’s effective tax rate.

These different taxes have different effects on people in different states. In Hawaiʻi for example, the General Excise Tax (GET) has a severe effect on low-income people who are disproportionately burdened by this tax. Although our state’s tax system includes a progressive income tax, which collects more revenue from wealthy people than from poor people, this is not enough to make up for the overall inequity in the system.

While this report shows that, in many ways, our policies are taking us in the wrong direction, it also points to some key adjustments that can be implemented to reverse the trend toward inequality and create a more productive system that allows the working class to participate in the economy while asking the wealthy to pay a fair share.

So what does make a good tax system, anyway? It isn’t just about how much money the system brings in, although that is an important part of it. A good tax system:

Should be simple for taxpayers to understand and comply with;

Should not play favorites among industries or areas;

Should be able to collect fees from non-residents who benefit from public services (e.g., visitors); and

Should be equitable in how it treats taxpayers at different income levels.

The best tax systems give appropriate breaks to low-income households to generate economic activity and collect more from those who have the most to spare. The ITEP report compares each state and the District of Columbia on an “inequality” index.

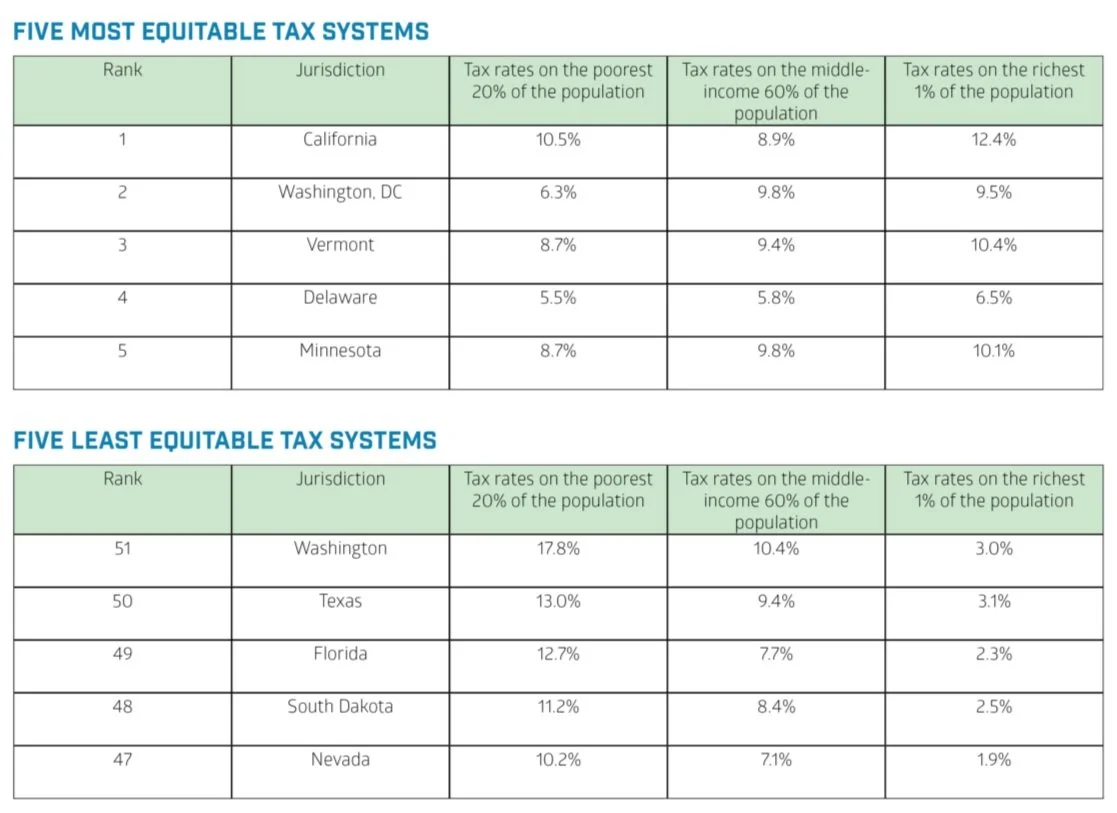

The most equitable systems have higher rates for richer taxpayers and lower rates for poorer ones. The inequitable systems take more from the poor and less from the rich. In worst-performing Washington state, the rate the poorest 20 percent of households pay is six times higher than that of top earners, while equitable California is one of a handful of jurisdictions where the rate is less for low-income households than it is on those earning most.

In a good tax system, the kind of tax matters. State income taxes are usually progressive, especially those that increase tax rates at higher incomes. Property taxes, the costs of which are often passed down to lower-income renters, are regressive in that lower income taxpayers pay a higher proportion of income towards them. Sales and excise taxes, like Hawaiʻi’s GET, are the most regressive, disproportionately affecting low income households because they spend more of their smaller incomes on necessary, taxable goods such as food, clothing, rent and household supplies.

The most equitable jurisdictions generally have higher income tax brackets and limit deductions for upper income households. They also use refundable credits and tend to be less reliant on sales and excise taxes. Seven of the 10 most equitable jurisdictions also have estate and inheritance taxes. Inequitable states have higher sales or excise taxes. They also have little or no income tax and do not provide refundable credits to low-income households.

How does Hawaiʻi’s tax system compare overall? Not great. We’re ranked 37th because we overtax the poorest households (a 15 percent effective tax rate) and under tax the richest (a 9 percent effective rate). The rate paid by the middle 60 percent is 11.5 percent. That 15 percent tax rate on the poor is especially harsh in Hawaiʻi because the GET is applied to virtually everything. This gives us the second highest effective tax rate in the nation for the lowest income households—only Washington’s 17.8 percent rate is harder on low-income earners. Hawaiʻi’s tax inequity is offset somewhat by a progressive income tax, the availability of tax credits and an estate tax.