Lessons from the Great Recession: How Hawaiʻi can better protect its communities during economic crises

The year 2009 marked one of the most severe economic downturns in recent history, forcing Hawaiʻi’s government to make painful budget decisions. Faced with plummeting tax revenues and growing demand for social services, the Lingle Administration implemented widespread cuts—including the infamous “Furlough Fridays,” which reduced public school instruction days by nearly a month. The move sparked outrage, with parents camping out in the governor’s office and even facing arrest in protest. While the administration had few easy options, the crisis revealed critical flaws in how the state manages fiscal emergencies.

As economic uncertainty persists, it’s essential to revisit these decisions—not just to understand what went wrong, but to prepare for future recessions. The choices made during economic contractions don’t just affect budgets; they shape the long-term well-being of communities.

The Collapse of Tax Revenue and Its Consequences

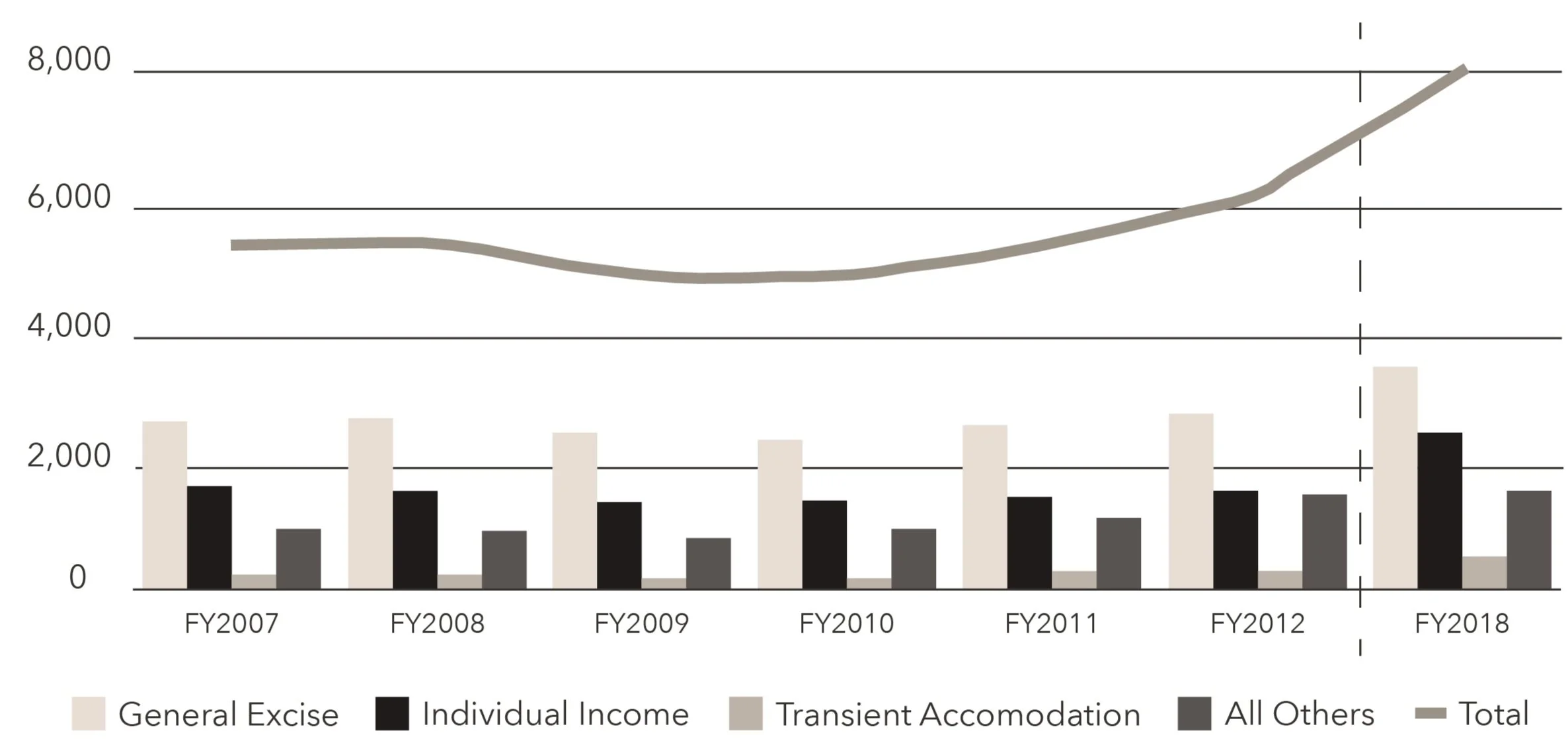

When the recession hit, Hawaiʻi’s tax revenues dropped sharply—$525 million less in 2009 than the previous year, with similar losses in 2010. It wasn’t until 2012 that collections recovered to pre-recession levels. This drastic shortfall forced the state to slash spending by over half a billion dollars—equivalent to $400 less per resident.

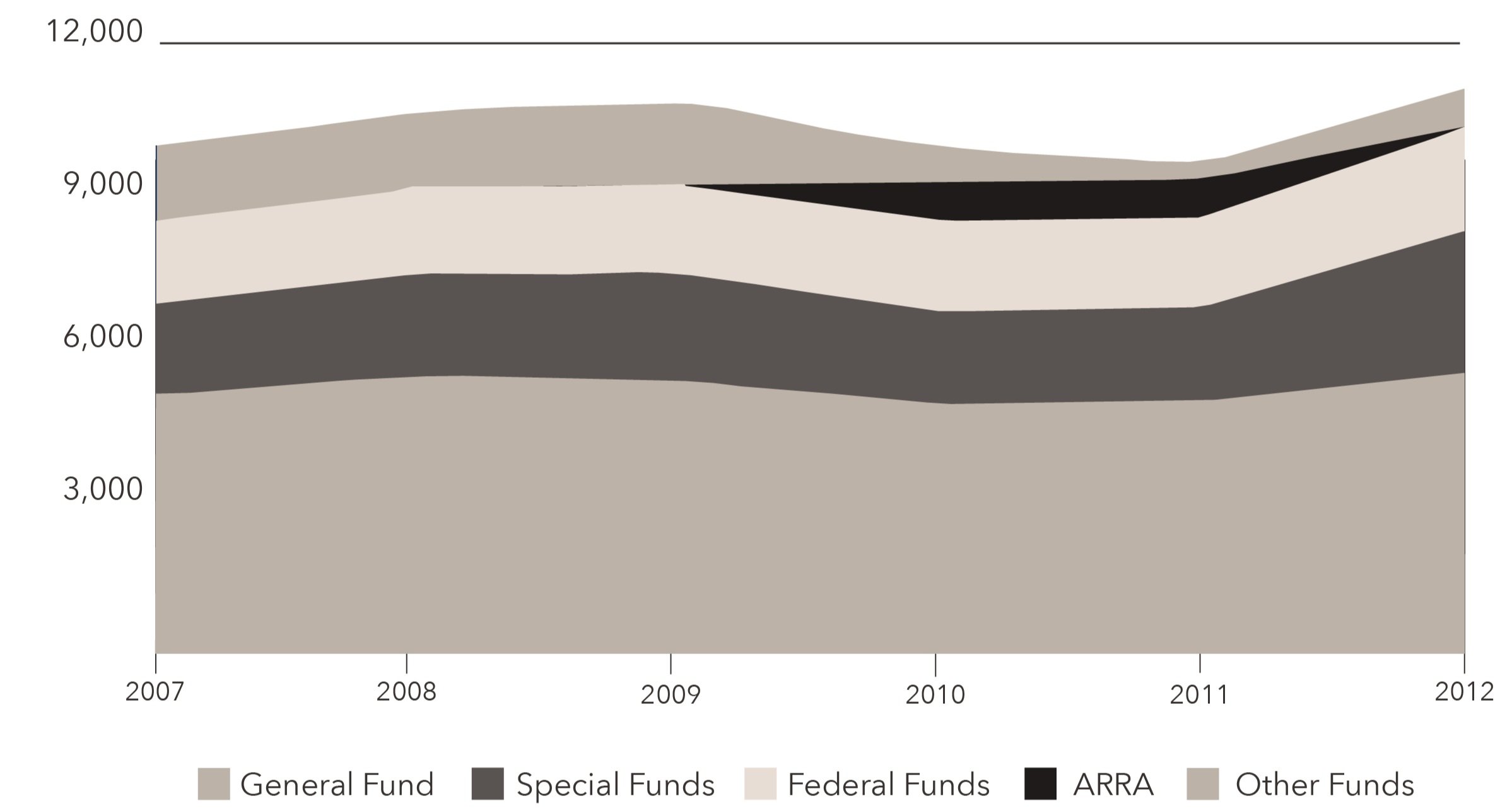

Federal stimulus funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) provided temporary relief, injecting $1.5 billion into Hawaiʻi’s budget between 2010 and 2012. These funds supported critical areas like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. However, even with this aid, the state still cut its budget by 5 percent in 2011—a reduction that would translate to $720 million in 2019 dollars.

Figure 1. Tax Collections by Category in $ Millions, FY2007–2012, Compared with FY2018

Figure 2. Hawaiʻi Budget by Means of Financing, FY2007–2012, in $ Millions

Not all cuts have the same impact. Reducing school days harmed far more families than, say, trimming administrative costs. Similarly, mental health services—already stretched thin—saw devastating reductions just when demand was rising. The state’s decision to largely preserve its own workforce while cutting contracts with nonprofit service providers worsened the fallout, as these organizations delivered essential aid efficiently.

The High Cost of Furloughs and Pay Cuts

To avoid mass layoffs, the state imposed furloughs—three unpaid days per month for most workers, and 17 days for teachers. While this saved $688 million over two years, the consequences were severe:

Students lost a full month of schooling, forcing parents to scramble for childcare.

Experienced public workers retired early, creating a leadership vacuum.

Pay cuts (5 percent in exchange for extra leave) in 2011 helped balance budgets but affected worker morale and retirement benefits.

The furlough crisis was eventually resolved by tapping the Hurricane Relief Fund to restore school days, but the damage lingered. The episode underscored a harsh reality: while furloughs preserve jobs, they can also weaken public services at the worst possible time.

The Growing Burden of Fixed Costs

A major challenge in recession budgeting is the rise of “fixed costs”—expenses like Medicaid, public worker pensions, and debt payments that are difficult to cut. In 2007, these consumed 40 percent of Hawaiʻi’s general fund. Today, they take up 50 percent, leaving little room to maneuver during a crisis.

During the last recession, the state renegotiated debt payments to save money—a smart but limited strategy. Building up the “Rainy Day” fund is another buffer, but Hawaiʻi’s current reserves ($376 million) would cover just nine days of operating expenses. Clearly, better preparation is needed.

Lasting Scars: Cuts to Health and Human Services

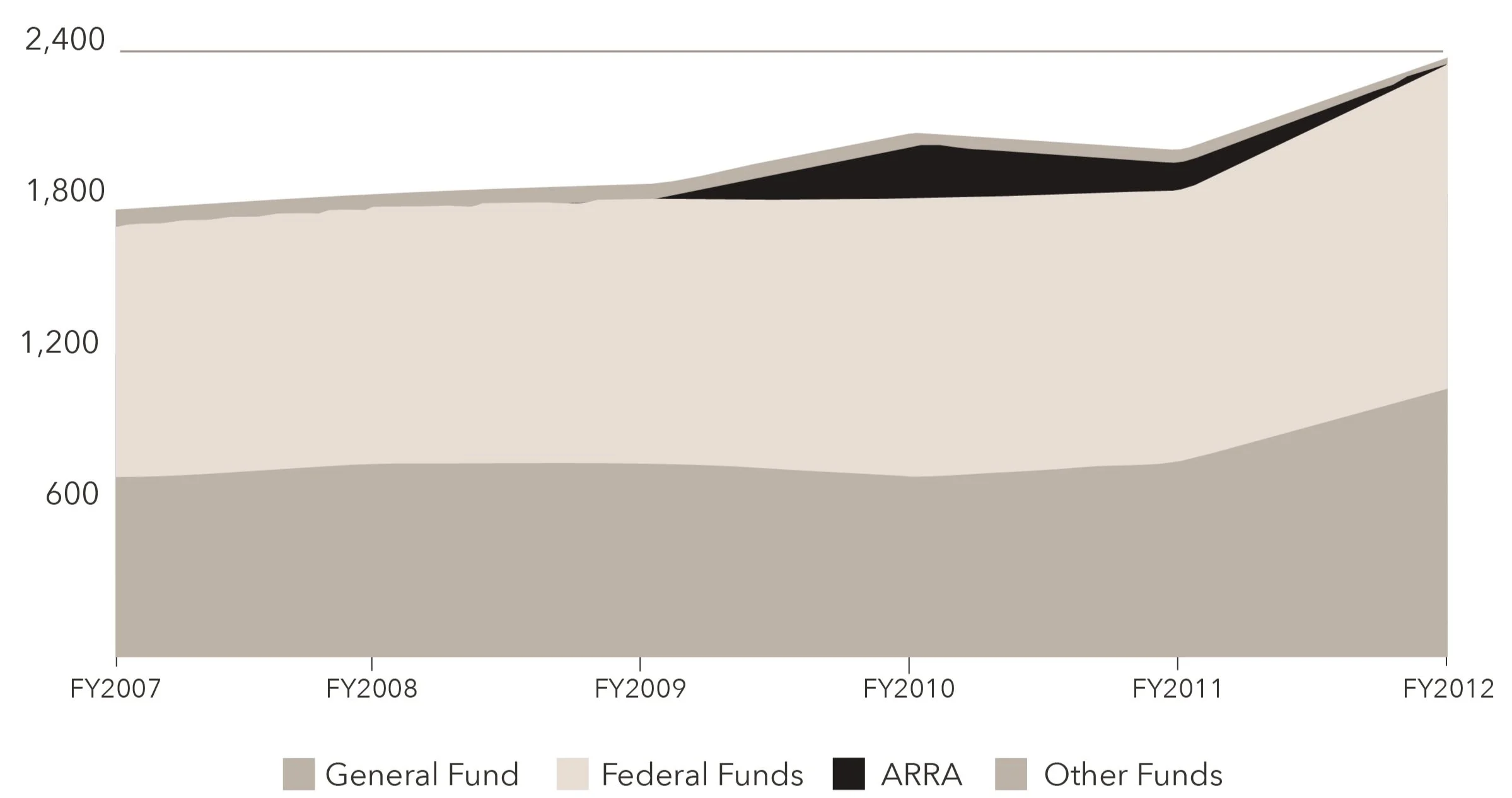

Some of the deepest cuts fell on services for the most vulnerable. The Department of Health (DOH) and Department of Human Services (DHS) saw funding drop just as demand surged:

Mental health services lost $33.6 million, leading to reduced counseling, closed group homes, and increased homelessness.

Nonprofit contracts were slashed by $4 million, eliminating programs like Healthy Start, which worked to prevent child abuse.

Medicaid and disability supports shrank, leaving many without critical care.

Figure 3. Hawaiʻi Department of Health Budget by Means of Finance, FY2007–2012, in $ Millions

Figure 4. Hawaiʻi Department of Human Services Budget by Means of Finance, FY2007–2012, in $ Millions

These cuts didn’t just hurt individuals—they shifted costs elsewhere. For example, reduced mental health funding led to a 7 percent increase in State Hospital patients, whose in-facility care is a far more expensive solution than community-based care.

Labor and Social Services: A Safety Net Unraveling

The Department of Labor also faced cuts, with lasting repercussions:

Disability Compensation programs (helping injured workers recover) lost $4.9 million, delaying returns to work.

The Office of Language Access saw a 29 percent cut, reducing support for non-English speakers.

Community aid programs for low-income families shrank by 9 percent, hindering self-sufficiency efforts.

Each of these reductions made it harder for struggling residents to regain stability—exactly when they needed help most.

Preparing for the Next Downturn

The lessons from 2009 are clear:

Prioritize essential services—Education, healthcare, and safety net programs must be shielded from the deepest cuts.

Expand financial buffers—Hawaiʻi’s Rainy Day fund is dangerously small; it should be strengthened.

Plan ahead for federal aid—If another stimulus comes, the state must be ready to deploy funds quickly and effectively.

Protect nonprofit partners—They deliver cost-effective services; cutting them only worsens crises.

Economic downturns are inevitable, but suffering isn’t. By learning from past mistakes—and acting now—Hawaiʻi can ensure that the next recession doesn’t devastate those least able to withstand it.

Download our complete report on the Great Recession below, with recommendations for the state to better prepare for the next downturn.