Broken Promises, Shattered Lives

The Case for Justice for Micronesians in Hawaiʻi

Executive Summary

The Compacts of Free Association, or COFA, are a series of treaties between the United States and the Federated States of Micronesia, the Republic of Palau and the Republic of the Marshall Islands. Under these treaties, the U.S. exercises strategic control of more than a million square miles of the Pacific between Hawaiʻi and Guam and significant economic control of the three nations.

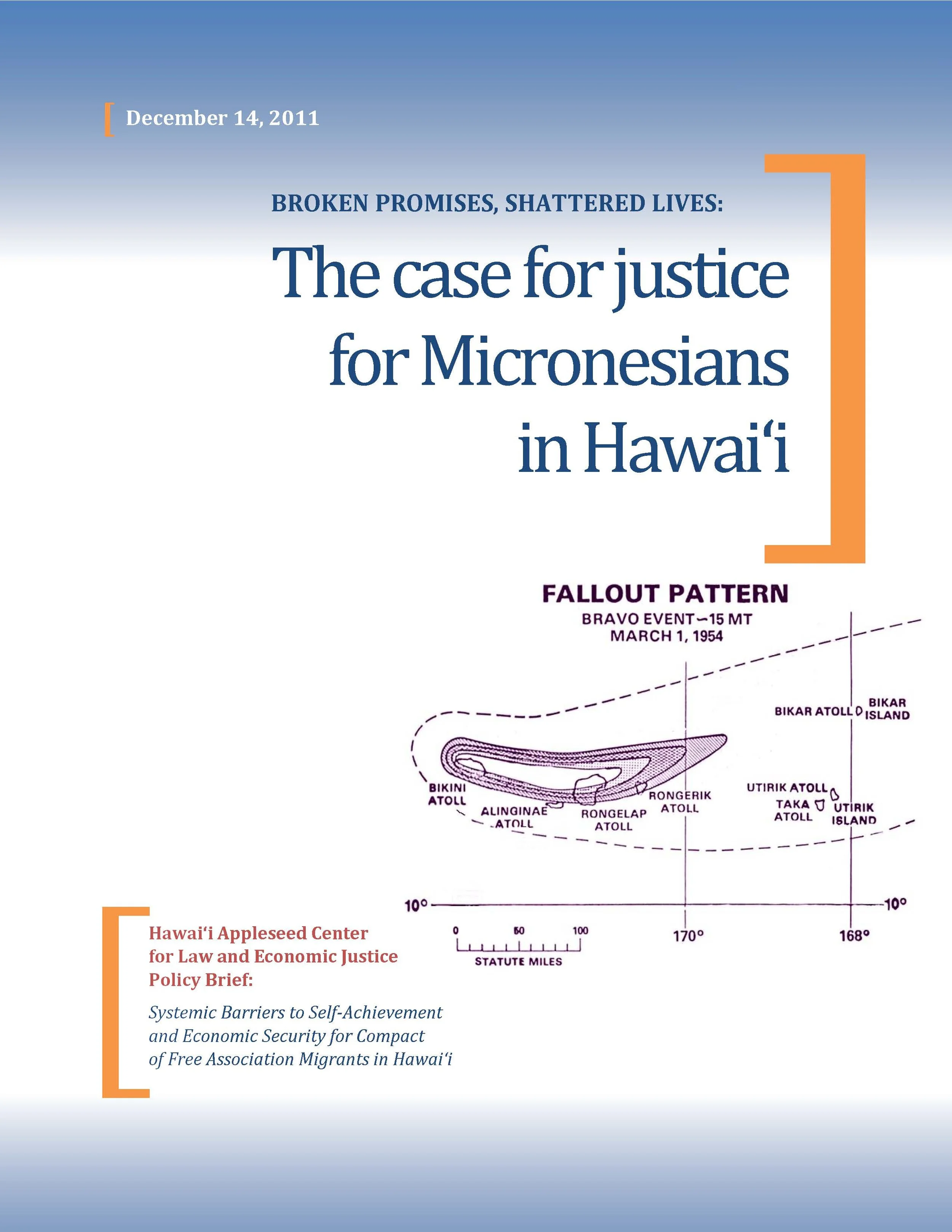

For many years, the U.S. tested nuclear weapons in Micronesia. At the nuclear test grounds at Eniwetok and Bikini in the Marshall Islands, 67 open-air atomic and hydrogen bombs were detonated. As a result, many islanders suffer disproportionately from serious health problems linked to nuclear weapons testing and ongoing U.S. occupation. Residents were forced to relocate, traditional agriculture became impossible on lands rendered unusable by fallout or military operations and the economy became dependent on the U.S. With few local jobs available, proportionally more recruits from COFA nations have joined the U.S. military than from any other state or territory.

COFA residents make many significant positive contributions to the U.S. economy and national security, yet they receive very few government benefits. They are legally eligible to work in the U.S.—and to pay state and federal taxes. However, unlike all other immigrants and U.S. citizens, COFA residents are excluded by law from ever receiving federal benefits such as Medicaid. Legal immigrants, refugees, victims of domestic violence, trafficking victims, immigrant victims of crime and asylum seekers are all eligible to receive these benefits, but COFA residents are not.

Some 15,000 COFA migrants now reside in Hawaiʻi, where they face many barriers to achieving assimilation and economic security, including language, social and cultural barriers, negative stereotyping and marginalization. This report details those barriers.

The State of Hawaiʻi annually receives Compact Impact funds—$11.2 million for fiscal year 2010, for example—to help pay for services to COFA residents, many of whom came here for healthcare that is unavailable in their home islands.

Until recently, the state provided care for them under programs such as QUEST, a managed care program where the state pays health plans to provide coverage of medical and mental health services. However, for economic reasons, the state created a new health program for Micronesian migrants in 2009 called Basic Health Hawaiʻi (BHH) that significantly reduced those benefits.

The BHH plan’s limited health care coverage was inadequate for disabled or seriously ill persons. Some patients used up all of their allotted visits to doctors simply to be diagnosed when confronted with complex illnesses. Disabled individuals and others often needed more doctor visits, prescriptions and access to medical procedures and devices than the plan allowed. Just as importantly, BHH did not cover critical services such as chemotherapy for cancer treatment and dialysis for kidney failure.

In November 2010, after Lawyers for Equal Justice (now the Hawaiʻi Appleseed Center for Law and Economic Justice) filed a class action suit on behalf of COFA migrants, Federal Court Judge Michael Seabright found the State violated the 14th amendment to the U.S. Constitution by specifically targeting COFA residents for cuts to medical services. He issued a preliminary injunction to reinstate benefits for COFA residents by January 2011. The state is now appealing this ruling.

If COFA residents are systemically denied access to healthcare, chronic conditions will fester until they become emergencies. Therefore, switching them to BHH could increase emergency service costs, overload emergency rooms and actually increase overall spending for healthcare.

The recent attempt by the State of Hawaiʻi to eliminate life-sustaining medical services is only one example of the structural barriers Micronesians families confront in their struggle to succeed. Others barriers include discrimination in housing and employment, in securing education for their children, and in obtaining critical social services to aid in their assimilation.

Despite their history of nuclear devastation, economic dependency, military service and relegation of territory, national security and sovereignty to the U.S., the citizens of the three COFA nations, under federal law, can never receive benefits that all other legal immigrants from countries that have never made such contributions need only wait five years to receive.

Micronesians are just the newest wave of immigrants to Hawaiʻi, a place that has always eventually welcomed, embraced and celebrated newcomers. Hawaiʻi needs a comprehensive plan to work against discrimination and negative stereotypes and to assist Micronesian assimilation, not to further marginalize the COFA community. It is time to reject stereotypes that demonize the COFA community and adopt policies that support their full integration into our state.

It is time for Hawaiʻi to be on the right side of history by improving opportunities for healthcare, education, employment, housing and social services for Micronesians living in our state. It is time for Hawaiʻi to accept and embrace the Micronesian migrant population, remove institutional barriers that limit assimilation, and willingly invest in our future together as one people.